For months leading up to November 3, 2020, Americans were bombarded with subtle messaging to outright insistence the election would be hacked, rigged, or in some way invalid. Non-partisan analysts within and outside the US government expressed confidence in the integrity of the systems and subsequently the veracity of the results. A mob unhindered by truth came to DC seeking to overrule the voice of the people to maintain the power structures in which they believe and on which their privilege depends, much like was seen in the Southern States after the American Civil War. In response, state legislatures have been debating and passing voter suppression and disenfranchisement laws to provide the voting minority more tools to overrule the will of the majority. These laws are being touted, much like their forebearers in the form of voter ID, poll taxes, and literacy tests, as necessary to safeguard the integrity of voting and the very Republic.

Similarly in the Frankincense industry, a predisposed conclusion was formulated and broadcast, then leveraged to maintain a status quo which serves established power structures and a privileged few.

In 2016, after two weeks in Somaliland and even less in the Harvest Region of Sanaag, a so-called researcher making promises of large payouts via an unaffiliated USAID program had garnered enough “data” through unverified and anecdotal in person interviews to declare the Boswellia trees in the region to be in crisis. Within this timeframe, this person who had actually been hired as an independent auditor for the initiation of a tree health study, successfully undermined and replaced the Somaliland leads of the study with a single “researcher” claiming to be a PhD but later found to have forged credentials. Late 2016 and early 2017, these findings were published globally across print and online reports as substantiated fact.1

After the goal of sounding the alarm – receiving funding from interested businesses – was in hand, these parties began a publishing spree. Typically their reports quote their preceding reports to create the illusion of impartiality and historical relevance. Some reports have been sent to “pay to publish” journals which herald themselves as peer reviewed. If a report is published within weeks of its date of writing, how vigorous would you consider its peer review to have been? As with the initial unverified interviews, these publications have served to create an echo chamber while acting to shore up the poor methods and erroneous conclusions upon which stands this house of cards.

It is from this unassailable high ground, this group has pronounced the only way forward is to rely on blockchain.

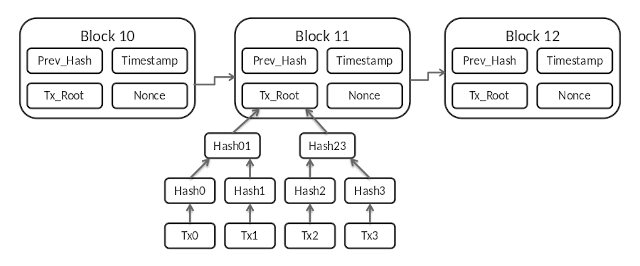

Let’s begin by unpacking what blockchain is: a linear distributed database using hashes for verifiability.

So in simpler terms, this is a way to record data in order of occurrence that becomes harder to change as time passes and the more copies there are.

In other words, time based entries are chained together with each link having a way to verify it has not been changed after its creation.

While these mechanisms can be automated for things that only exist in the digital space, how can blockchain be effectively applied in the physical world?

Let’s consider an example. Toyota, the world’s largest automaker and originator of just in time (JIT) inventory, has spent the past 4-5 years to evaluate implementing blockchain for components that are made in a handful of known locations by known suppliers serving long standing contracts. Many of its components originate via its partially owned subsidiaries such as Denso. Toyota is the 10th largest corporation in the world with exceptional computational and IT resources. This speaks to the financial, human, and energy resources needed for blockchain use. Initially, they anticipate using this technology for data sharing such as for maintenance records and to aggregate vehicle sensor observations with other automakers towards the goal of autonomous operation.2,3,4,5

Now let’s compare this robust physical and digital infrastructure to the millenia old art of oleo gum resin harvesting in East Africa. Annual collection takes place in rural and rugged terrain, typically the Boswellia trees are visited 5-6 times over the course of a six week harvest. IT infrastructure is non-existent save for an occasional mobile signal. The harvester touching each tree is the person who is expected to digitize the tree ID, harvest date, yield amount and so forth. Furthermore, it is vital to understand these regions have no formal electric grid. At most residents rely on intermittent diesel generators or some small scale solar panels to recharge phones or perhaps run a radio. This inherently means any servers holding blockchain data will be housed elsewhere, limiting accountability to the communities reliant on these resins. Considering this, we can begin to see how blockchain as a “solution” to sustainable harvesting is deeply flawed.

And yet this fails to address the hundreds of years of upside down supply chains which have siphoned and continue to suck the resources of a continent to sustain post-colonial economies without regard for the impoverishment these activities perpetuate. Not to mention, ignores the input and expertise of the landowners and harvesters who have been stewards of these trees for generations. Who truly believes frankincense harvesters, the majority of whom don’t even use email and may have a non-touch screen pay as you go mobile phone, are going to adopt this new technology successfully?

So why try to shoehorn a technical solution onto an ethics problem?

As has been evident the past decade with greenwashed marketing messages or starting decades before with single percentage contributions to social responsibility initiatives: providing an unnecessarily complex solution to a simple problem serves to appease the buying public while confusing the real underlying issues so corporate bad actors can continue to pillage unabated.

The proven mechanisms providing economic justice over the past century include:

- Organized Labor: this can and must be expanded among rural producers.

- Collective Bargaining: as fair trade principles look to establish annual sustainable pricing, organized producers can do the same with or without paying per product to international auditors.

- Corporate Accountability: including supply transparency such as source, cost and upstream value. This must become required of all public companies and encouraged for all private.

- Profit Sharing: companies know the net profits from their products, these profits must be shared with those producing the ingredients for these products if we want to create an equitable world.

- Oversight: government and NGOs roles are to ensure these tools are used as intended and to fine or shame bad actors.

These common sense solutions are available to ensure producers share in the wealth of their goods while applying ethical standards to corporations regardless of size.

Any solution which is applied on behalf of growing and harvesting communities without their vision and voices is more likely to further disenfranchise and impoverish than to reverse global inequities.

The history of these resins shows time and again how multinational concerns use their market position to drive prices down at the source in order to accumulate wealth for themselves.

While I’m happy to discuss my decades of Systems Engineering experience beginning during my undergraduate studies, the point is: Applying technology for the sake of technology has no inherent value.

Much like providing self-serving solutions to a manufactured crisis does not benefit the greater good.

The goal of Boswellness is to empower indigenous producers leading the way forward in both ecological and economic terms. We have the opportunity to amplify and uplift the voices of those touching these trees and other plants while creating inclusive solutions.

Sources

- CITES Twenty-fifth meeting of the Plants Committee Online, 2-4, 21 and 23 June 2021. Specifically pg. 2 section 4.2b, pg. 7, pg. 9 section 15B, pg. 14 Annex 6 section 1. https://cites.org/sites/default/files/eng/com/pc/25/Documents/E-PC25-25-Add.pdf

- Toyota Motor Corporation, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toyota

- Toyota pushes into blockchain tech to enable the next generation of cars, Tech Crunch, https://techcrunch.com/2017/05/22/toyota-pushes-into-blockchain-tech-to-enable-the-next-generation-of-cars/

- Toyota Blockchain Lab, Corporate Press Release, https://global.toyota/en/newsroom/corporate/31827481.html

- DENSO Corporation, Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Denso